On September 29, 2005, John G. Roberts, Jr., was sworn in as the 17th Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. You can watch his swearing in ceremony here.

This seems like a nice opportunity to spotlight all of our nation’s chief justices (note: all images and biographical information are provided below from the Supreme Court Historical Society):

(1) Chief Justice John Jay, 1789-1795

JOHN JAY was born on December 12, 1745, in New York, New York, and grew up in Rye, New York. He was graduated from King’s College (Now Columbia University) in 1764. He read law in a New York law firm and was admitted to the bar in 1768. Jay served as a delegate to both the First and Second Continental Congresses, and was elected President of the Continental Congress in 1778. He also served in the New York State militia. In 1779, Jay was sent on a diplomatic mission to Spain in an effort to gain recognition and economic assistance for the United States. In 1783, he helped to negotiate the Treaty of Paris, which marked the end of the Revolutionary War. Jay favored a stronger union and contributed five essays to The Federalist Papers in support of the new Constitution. President George Washington nominated Jay the first Chief Justice of the United States on September 24, 1789. The Senate confirmed the appointment on September 26, 1789. In April 1794, Jay negotiated a treaty with Great Britain, which became known as the Jay Treaty. After serving as Chief Justice for five years, Jay resigned from the Supreme Court on June 29, 1795, and became Governor of New York. He declined a second appointment as Chief Justice in 1800, and President John Adams then nominated John Marshall for the position.

(2) Chief Justice John Rutledge, 1795

JOHN RUTLEDGE was born in Charleston, South Carolina, in September 1739. He studied law at the Inns of Court in England, and was admitted to the English bar in 1760. In 1761, Rutledge was elected to the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly. In 1764, he was appointed Attorney General of South Carolina by the King’s Governor and served for ten months. Rutledge served as the youngest delegate to the Stamp Act Congress of 1765, which petitioned King George III for repeal of the Act. Rutledge headed the South Carolina delegation to the Constitutional Convention in 1787 and served as a member of the South Carolina Ratification Convention the following year. On September 24, 1789, President George Washington nominated Rutledge one of the original Associate Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States. The Senate confirmed the appointment two days later. After one year on the Supreme Court, Rutledge resigned in 1791 to become Chief Justice of South Carolina’s highest court. On August 12, 1795, President George Washington nominated Rutledge Chief Justice of the United States. He served in that position as a recess appointee for four months, but the Senate refused to confirm him.

(3) Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth, 1796-1800

OLIVER ELLSWORTH was born on April 29, 1745, in Windsor, Connecticut. Ellsworth attended Yale College until the end of his sophomore year, and then transferred to the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), where he was graduated in 1766. He read law in a law office for four years and was admitted to the bar in 1779. Ellsworth was a member of the Connecticut General Assembly from 1773 to 1776. From 1777 to 1784, he served as a delegate to the Continental Congress and worked on many of its committees. After service on the Connecticut Council of Safety and the Governor’s Council, he became a Judge of the Superior Court of Connecticut in 1785. As a delegate to the Federal Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787, Ellsworth helped formulate the “Connecticut Compromise,” which resolved a critical debate between the large and small states over representation in Congress. Ellsworth was elected to the First Federal Congress as a Senator. There he chaired the committee that drafted the Judiciary Act of 1789, which established the federal court system. On March 3, 1796, President George Washington nominated Ellsworth Chief Justice of the United States and the Senate confirmed the appointment the following day. He resigned from the Supreme Court on September 30, 1800.

(4) Chief Justice John Marshall, 1801-1835

JOHN MARSHALL was born on September 24, 1755, in Germantown, Virginia. Following service in the Revolutionary War, he attended a course of law lectures conducted by George Wythe at the College of William and Mary and continued the private study of law until his admission to practice in 1780. Marshall was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates in 1782, 1787, and 1795. In 1797, he accepted appointment as one of three envoys sent on a diplomatic mission to France. Although offered appointment to the United States Supreme Court in 1798, Marshall preferred to remain in private practice. Marshall was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1799, and in 1800 was appointed Secretary of State by President John Adams. The following year, President Adams nominated Marshall Chief Justice of the United States, and the Senate confirmed the appointment on January 27, 1801. Notwithstanding his appointment as Chief Justice, Marshall continued to serve as Secretary of State throughout President Adams’ term and, at President Thomas Jefferson’s request, he remained in that office briefly following Jefferson’s inauguration. Marshall served as Chief Justice for 34 years, the longest tenure of any Chief Justice. During his tenure, he helped establish the Supreme Court as the final authority on the meaning of the Constitution.

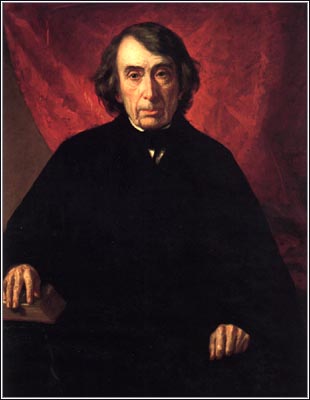

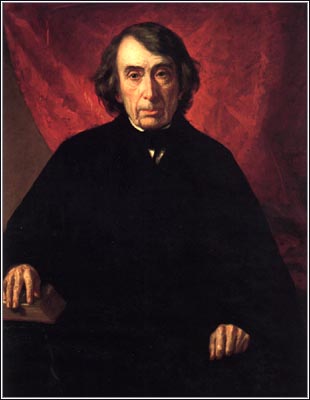

(5) Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney, 1836-1864

ROGER BROOKE TANEY was born in Calvert County, Maryland, on March 17, 1777. He was graduated from Dickinson College in 1795. After reading law in a law office in Annapolis, Maryland, he was admitted to the bar in 1799. In the same year, he was elected to the Maryland House of Delegates. Defeated for re-election, he was elected to the State Senate in 1816 and served until 1821. In 1823, Taney moved to Baltimore, where he continued the practice of law. From 1827 to 1831, Taney served as Attorney General for the State of Maryland. In 1831, Taney was appointed Attorney General of the United States by President Andrew Jackson. On September 23, 1833, Taney received a recess appointment as Secretary of the Treasury. When the recess appointment terminated, Taney was formally nominated to serve in that position, but the Senate declined to confirm the appointment in 1834. In 1835, Taney was nominated as Associate Justice by President Jackson to succeed Justice Duvall, but the Senate failed to confirm him. On December 28, 1835, President Jackson nominated Taney Chief Justice of the United States. The Senate confirmed the appointment on March 15, 1836. Taney served as Chief Justice for twenty-eight years.

(6) Chief Justice Salmon Portland Chase, 1864-1873

SALMON PORTLAND CHASE was born in Cornish, New Hampshire, on January 13, 1808, and was raised in Ohio. He returned to New Hampshire to attend Dartmouth College and was graduated in 1826 at the age of eighteen. He then moved to Washington, D.C., where he read law under Attorney General William Wirth. Chase was admitted to the bar in 1829 and moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, where he worked as a lecturer, writer, and editor while he established a legal practice. Chase became involved in the anti-slavery movement, and in 1848 he helped to write the platform of the Free Soilers Party. In 1848, the Ohio legislature elected Chase to the United States Senate, where he served one six-year term. In 1855, he was elected to a four-year term as Governor of Ohio, and in 1860 he was re-elected to the United States Senate. Chase resigned his Senate seat after only two days to accept a wartime appointment by President Abraham Lincoln as Secretary of the Treasury. He resigned from that post in June 1864. Six months later, on December 6, 1864, President Lincoln nominated Chase Chief Justice of the United States. The Senate confirmed the appointment on December 15, 1864. Chase served as Chief Justice for eight years

(7) Chief Justice Morrison R. Waite, 1874-1888

MORRISON R. WAITE was born in Lyme, Connecticut on November 29, 1816. He was graduated from Yale College in 1837 and moved to Ohio to read law with an attorney in Maumee City. Waite was admitted to the bar in 1839 and practiced in Maumee City until 1850. He then moved to Toledo, where he practiced until 1874. Waite was elected to the Ohio General Assembly in 1850 and served one term. He ran unsuccessfully for the United States House of Representatives in 1846 and 1862. Waite declined an appointment to the Ohio Supreme Court in 1863. In 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Waite to a Commission established to settle United States claims against Great Britain, arising out of the latter’s assistance to the Confederacy during the Civil War. The proceedings resulted in an award of $15.5 million in compensation to the United States. Upon his return from Europe, Waite was elected to the Ohio Constitutional Convention of 1873 and was unanimously selected to serve as its president. During the Convention, on January 19, 1874, President Grant nominated Waite Chief Justice of the United States. The Senate confirmed the appointment two days later. Waite served as Chief Justice for fourteen years.

(8) Chief Justice Melville Weston Fuller, 1888-1910

MELVILLE WESTON FULLER was born in Augusta, Maine, on February 11, 1833, and was graduated from Bowdoin College in 1853. Fuller read law in Bangor, Maine, and was admitted to the bar after six months of study at Harvard Law School. In 1855, Fuller began to practice law in Augusta, Maine, and was elected President of the Augusta Common Council and appointed city solicitor. In 1856, Fuller moved west to Chicago, where he established a law practice and became active in politics. He was elected to the Illinois House of Representatives in 1863 and served one term. In succeeding years he was offered the positions of Chairman of the Civil Service Commission and Solicitor General of the United States but declined both. President Grover Cleveland nominated Fuller Chief Justice of the United States on April 30, 1888. The Senate confirmed the appointment on July 20, 1888. While on the Court, Fuller served on the Venezuela-British Guiana Border Commission and the Court of Permanent Arbitration at the Hague. Fuller served twenty-one years as Chief Justice.

(9) Chief Justice Edward Douglas White, 1910-1921

EDWARD DOUGLAS WHITE was born in the Parish of Lafourche, Louisiana, on November 3, 1845. While White was studying at Georgetown College (now Georgetown University) the Civil War began and he returned home to join the Confederate Army. He was captured in 1863 by Union troops and remained in captivity until the end of the War. Upon his release in 1865, White read law and attended the University of Louisiana. He was admitted to the bar in 1866 and established a law practice in New Orleans. White was elected to the Louisiana State Senate in 1874, and from 1878 to 1880 he served on the Louisiana Supreme Court. In 1891, the State Legislature elected him to the United States Senate. President Grover Cleveland nominated White to the Supreme Court of the United States on February 19, 1894. The Senate confirmed the appointment the same day. White had served for sixteen years on the Court when, on December 12, 1910, President William H. Taft nominated him Chief Justice of the United States. The Senate confirmed the appointment the same day. White was the first Associate Justice to be appointed Chief Justice. White served on the Court for a total of twenty-six years, ten of them as Chief Justice.

(10) Chief Justice William Howard Taft, 1921-1930

WILLIAM HOWARD TAFT was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, on September 15, 1857. He was graduated from Yale University in 1878 and from Cincinnati Law School in 1880. Taft began his career in private practice in Cincinnati. After serving as an assistant prosecutor and a Judge of the Ohio Superior Court, he was appointed Solicitor General of the United States in 1890. From 1892 to 1900, Taft served as a Judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit. In 1901, he was named Civilian Governor of the Philippines. In 1904, President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Taft Secretary of War. Taft was elected President of the United States in 1908 and served one term. After leaving the White House, Taft taught constitutional law at Yale University and appeared frequently on the lecture circuit. From 1918 to 1919, he served as Joint Chairman of the War Labor Board. President Warren G. Harding nominated Taft Chief Justice of the United States on June 30, 1921. The senate confirmed the appointment the same day, making Taft the only person in history to have been both President and Chief Justice. As Chief Justice he focused on the administration of justice and at his request Congress created the Conference of Senior Circuit (Chief) Judges to oversee court administration. This body became the Judicial Conference of the United States. Taft retired from the Court on February 3, 1930, after serving eight years as Chief Justice.

(11) Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, 1930 – 1941

CHARLES EVANS HUGHES was born in Glens Falls, New York, on April 11, 1862. He was graduated in 1881 from Brown University and received a law degree from Columbia University in 1884. For the next twenty years, he practiced law in New York, New York, with only a three-year break to teach law at Cornell University. Hughes was elected Governor of New York in 1905 and re-elected two years later. On April 25, 1910, President William H. Taft nominated Hughes to the Supreme Court of the United States, and the Senate confirmed the appointment on May 2, 1910. Hughes resigned from the Court in 1916 upon being nominated by the Republican Party to run for president. After losing the election to Woodrow Wilson, he returned to his law practice in New York. Hughes served as Secretary of State from 1921 to 1925. He subsequently resumed his law practice while serving in the Hague as a United States delegate to the Permanent Court of Arbitration from 1926 to 1930. On February 3, 1930, President Herbert Hoover nominated Hughes Chief Justice of the United States, and the Senate confirmed the appointment on February 13, 1930. He served as Chairman of the Judicial Conference of the United States from 1930 to 1941. Hughes retired on July 1, 1941, after serving eleven years as Chief Justice.

(12) Chief Justice Harlan Fiske Stone, 1941-1946

HARLAN FISKE STONE was born on October 11, 1872, in Chesterfield, New Hampshire. He was graduated from Amherst College in 1894. After teaching high school chemistry for one year, he studied law at Columbia University, where he received his degree in 1898. In 1899, Stone was admitted to the bar and joined a New York law firm. For the next twenty-five years he divided his time between his practice and a career as a professor of law at Columbia University. He became Dean of the Law School in 1910 and remained in that position for thirteen years. In 1924, President Calvin Coolidge appointed Stone Attorney General of the United States. The following year, on January 5, 1925, President Coolidge nominated him to the Supreme Court of the United States. The Senate confirmed the appointment February 5, 1925. After sixteen years of service as an Associate Justice, Stone was nominated Chief Justice of the United States by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on June 12, 1941. He served as Chairman of the Judicial Conference of the United States from 1941 to 1946. Stone served a total of twenty years on the Court.

(13) Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson, 1946-1953

FRED M. VINSON was born in Louisa, Kentucky, on January 22, 1890. He was graduated from Centre College in 1909 and from its Law School two years later. In 1911, Vinson was admitted to the bar and began to practice law in Ashland, Kentucky. Vinson became City Attorney of Ashland and, in 1921, Commonwealth’s Attorney for the County. He was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1924 and was re-elected in 1926. He resumed his Ashland practice for two years and then won re-election to the House for four consecutive terms. In 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed him to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. Vinson served the Roosevelt Administration during World War II in a succession of positions starting in 1943: Director of the Office of Economic Stabilization, Administrator of the Federal Loan Agency, and Director of the Office of War Mobilization and Reconversion. In 1945, shortly after the end of the War, President Harry Truman appointed Vinson Secretary of the Treasury. On June 6, 1946, President Truman nominated Vinson Chief Justice of the United States. The Senate confirmed the appointment on June 20, 1946. He served as Chairman of the Judicial Conference of the United States from 1946 to 1953. Vinson served for seven years as Chief Justice.

(14) Chief Justice Earl Warren, 1953-1969

EARL WARREN was born in Los Angeles, California, on March 19, 1891. He was graduated from the University of California in 1912 and went on to receive a law degree there in 1914. He practiced for a time in law offices in San Francisco and Oakland. In 1919, Warren became Deputy City Attorney of Oakland, beginning a life in public service. In 1920, he became Deputy Assistant District Attorney of Alameda County. In 1925, he was appointed District Attorney of Alameda County, to fill an unexpired term, and was elected and re-elected to the office in his own right in 1926, 1930, and 1934. In 1938, he was elected Attorney General of California. In 1942, Warren was elected Governor of California, and he was twice re-elected. In 1948, he was the Republican nominee for Vice President of the United States, and in 1952, he sought the Republican party’s nomination for President. On September 30, 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower nominated Warren Chief Justice of the United States under a recess appointment. The Senate confirmed the appointment on March 1, 1954. Warren served as Chairman of the Judicial Conference of the United States from 1953 to 1969 and as Chairman of the Federal Judicial Center from 1968 to 1969. He also chaired the commission of inquiry into the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963. He retired on June 23, 1969, after fifteen years of service.

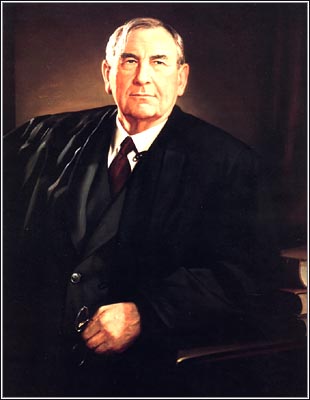

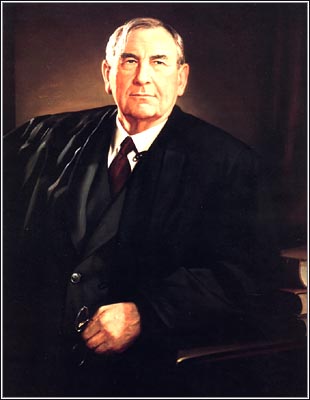

(15) Chief Justice Warren E. Burger, 1969-1986

WARREN E. BURGER was born in St. Paul, Minnesota, on September 17, 1907. After pre-legal studies at the University of Minnesota in high classes, he earned a law degree in 1931 from the St. Paul College of Law (now William Mitchell College of Law) by attending four years of night classes while working in the accounting department of a life insurance company. He was appointed to the faculty of his law school upon graduation and remained on the adjunct faculty until 1946. Burger practiced with a St. Paul law firm from 1931 to 1953. In 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed Burger Assistant Attorney General of the United States, Chief of the Civil Division of the Department of Justice. In 1955, President Eisenhower appointed him to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, where he served until 1969. President Richard M. Nixon nominated Burger Chief Justice of the United States on May 22, 1969. The Senate confirmed the appointment on June 9, 1969, and he took office on June 23, 1969. In July 1985, President Ronald Reagan appointed Burger Chairman of the Commission on the Bicentennial of the United States Constitution. As Chief Justice he served as Chairman of the Judicial Conference of the United States and as Chairman of the Federal Judicial Center from 1969 to 1986. Burger retired from the Court on September 26, 1986, after seventeen years of service, and continued to direct the Commission on the Bicentennial of the United States Constitution from 1986 to 1992.

(16) Chief Justice William Hubbs Rehnquist, 1986-2005

WILLIAM HUBBS REHNQUIST was born in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, October 1, 1924. He served in the Army Air Corps during World War II as a weather observer in North Africa. Following the war, he attended college on the GI Bill, earning both a B.A. (Phi Beta Kappa) and M.A. in political science at Stanford University in 1948. Rehnquist received a second M.A., in government, from Harvard two years later. He then entered Stanford Law School, where he graduated first in his class in 1952. (The student who ranked third was Sandra Day, who later joined him on the Supreme Court.) In 1952, Rehnquist clerked for Justice Robert Jackson. Rehnquist served as assistant attorney general for the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel under the Nixon Administration. Rehnquist served on the Supreme Court for 33 years, first as an Associate Justice from 1972 to 1986, and then as the 16th Chief Justice of the United States from 1986 until his death in 2005.

(17) Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., 2005 – Present

JOHN G. ROBERTS, Jr. was born in Buffalo, New York, January 27, 1955. He married Jane Marie Sullivan in 1996 and they have two children – Josephine and Jack. He received an A.B. from Harvard College in 1976 and a J.D. from Harvard Law School in 1979. He served as a law clerk for Judge Henry J. Friendly of the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit from 1979–1980 and as a law clerk for then-Associate Justice William H. Rehnquist of the Supreme Court of the United States during the 1980 Term. He was Special Assistant to the Attorney General, U.S. Department of Justice from 1981–1982, Associate Counsel to President Ronald Reagan, White House Counsel’s Office from 1982–1986, and Principal Deputy Solicitor General, U.S. Department of Justice from 1989–1993. From 1986–1989 and 1993–2003, he practiced law in Washington, D.C. He was appointed to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in 2003. President George W. Bush nominated him as Chief Justice of the United States, and he took his seat September 29, 2005.