On September 26, 1789, the U.S. Senate voted to confirm John Jay, John Rutledge, William Cushing, John Blair, Robert Harrison, and James Wilson as the first justices of the United States Supreme Court.

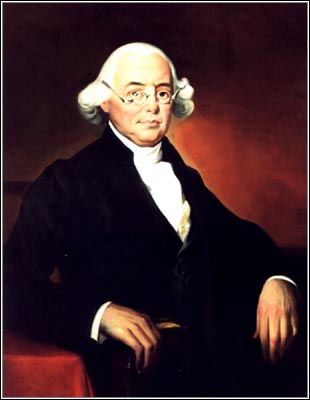

John Jay was confirmed as the nation’s first Chief Justice. Jay served as a delegated to both the First and Second Continental Congresses, and was elected president of the Continental Congress in 1778. He also contributed five essays to The Federalist (now known as The Federalist Papers), and was a stronger supporter of the federal Constitution of 1787. After serving as Chief Justice for five years, Jay resigned from the Supreme Court on June 29, 1795, and became Governor of New York. He declined a second appointment as Chief Justice in 1800, and President John Adams then nominated John Marshall for the position.

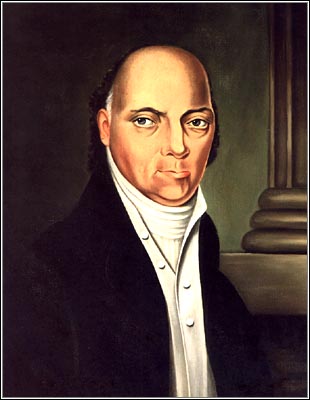

John Rutledge was elected to the South Carolina Commons House of Assembly. In 1764, he was appointed Attorney General of South Carolina by the King’s Governor and served for ten months. Rutledge served as the youngest delegate to the Stamp Act Congress of 1765.He was a member South Carolina delegation to the Constitutional Convention in 1787 and served as a member of the South Carolina Ratification Convention the following year. After one year on the Supreme Court, Rutledge resigned in 1791 to become Chief Justice of South Carolina’s highest court. On August 12, 1795, President George Washington nominated Rutledge Chief Justice of the United States. He served in that position as a recess appointee for four months, but the Senate refused to confirm him.

William Cushing served as Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court from 1780 to 1789. He strongly supported ratification of the U.S. Constitution and served as Vice Chairman of the Massachusetts Ratification Convention. Cushing served on the Court for 20 years.

John Blair began his public service in 1766 as a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses. In 1770, he resigned from the House to become Clerk of the Governor’s Council. Blair was a delegate to the Virginia Convention of 1776, which drafted the State Constitution. Blair became a Judge of the Virginia General Court in 1777 and was elevated to Chief Judge in 1779. From 1780 to 1789, he served as a Judge of the First Virginia Court of Appeals. Blair was a delegate to the Federal Constitutional Convention of 1787 and was one of three Virginia delegates to sign the Constitution. He was also a delegate to the Virginia Ratification Convention of 1788. He served on the Court for only 5 years, and resigned due to the rigors of circuit riding and ill health.

Robert Harrison served as the Chief Justice of the General Court of Maryland from 1781 to 1789.Harrison, ultimately, declined to serve as an associate justice, citing health reasons. The seat eventually went to James Iredell.

James Wilson was elected a delegate to the First Continental Congress in 1775 and was a signer of the Declaration of Independence. He also served as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress. As a delegate to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia in 1787, Wilson was a member of the committee that produced the first draft of the Constitution. He signed the finished document on September 17, 1787, and later served as a delegate to the Pennsylvania Ratification Convention. He served on the Court for eight years.

(Biographical information of the justices was provided by the Supreme Court Historical Society).